Cliff dwellings along the San Francisco and Gila Rivers are evidence of an advanced civilization that existed long before Caesar ruled Rome. Many specimens of pottery and stone implements are still to be found in these ancient dwelling places. In the mid-1500s, both Fray Marcos de Niza and Francisco Vasquez de Coronado passed through the area, following the San Pedro north to the Gila River. Geronimo was born in 1829 near the confluence of Eagle Creek and the San Francisco and Gila Rivers.

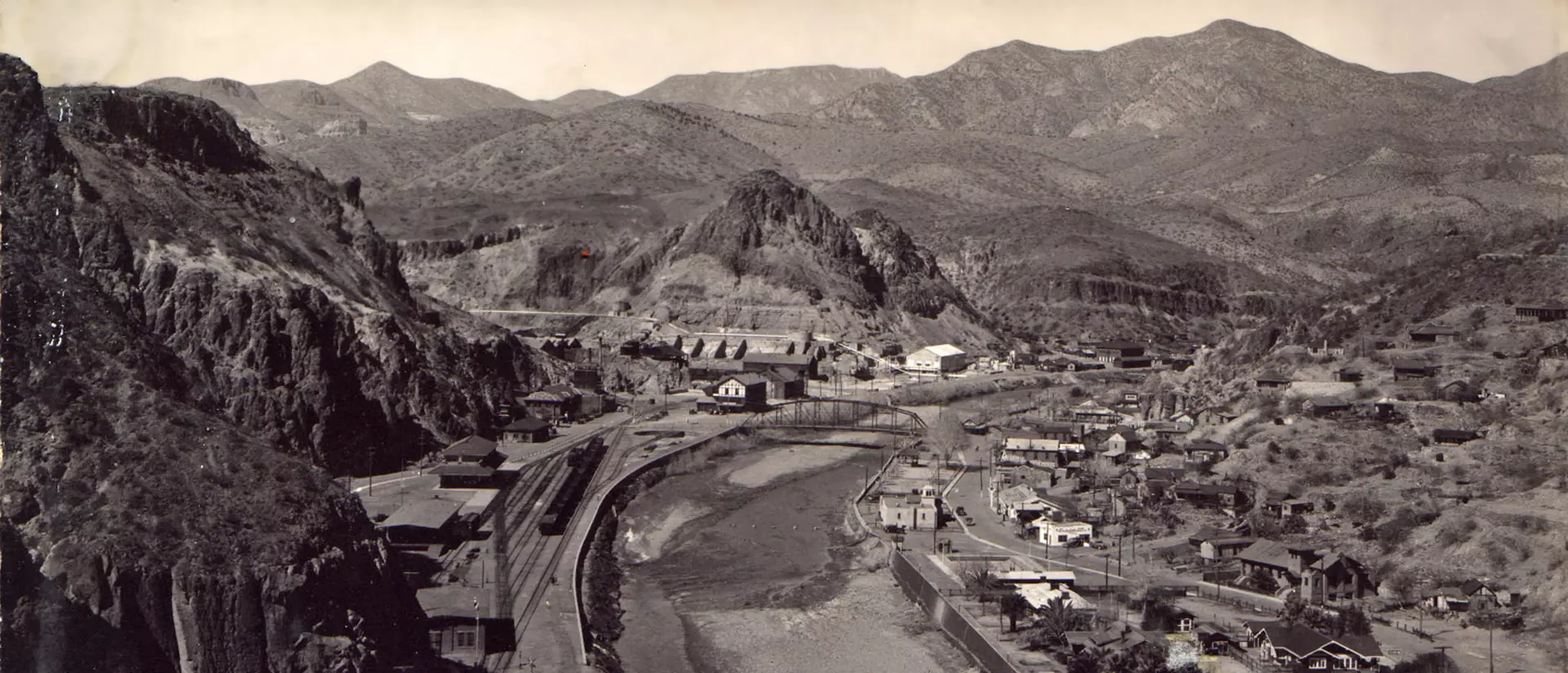

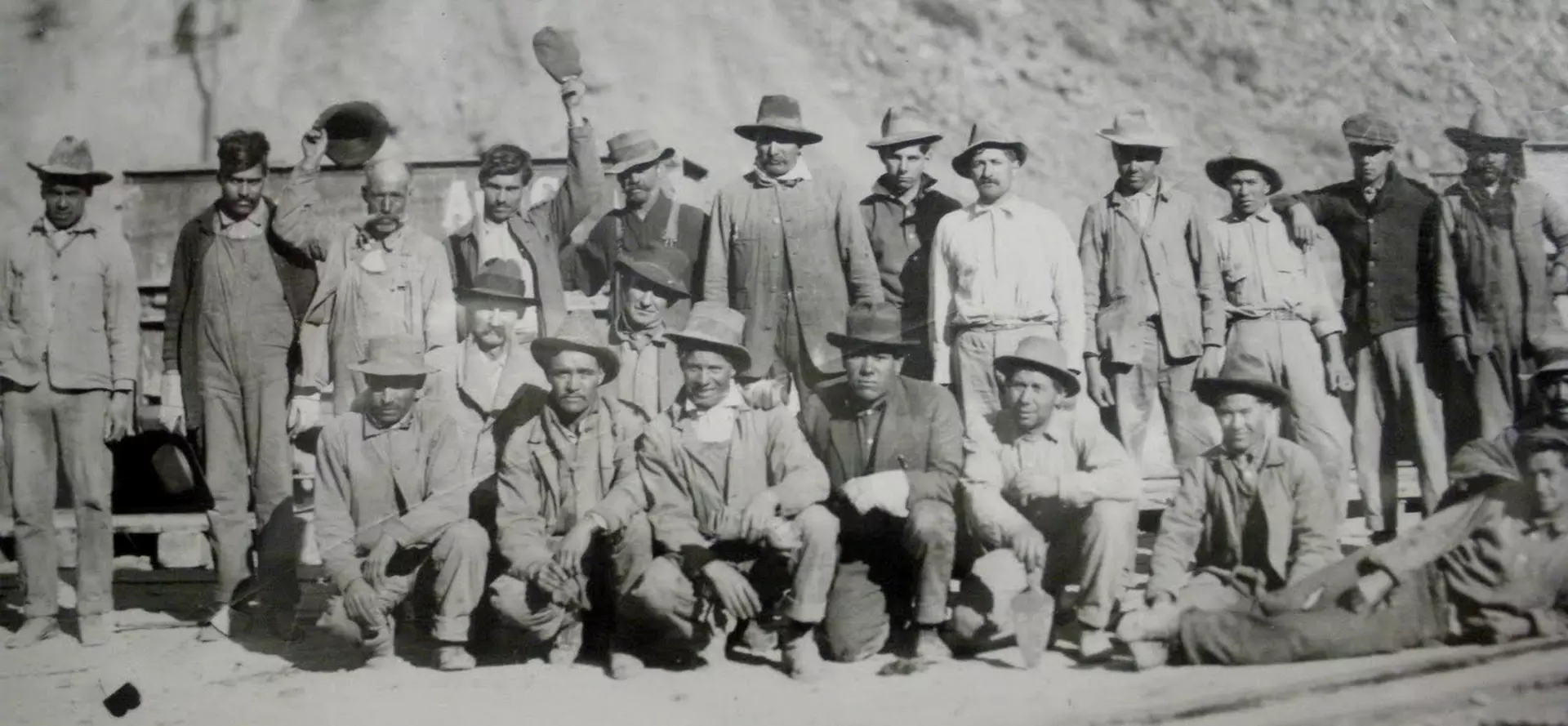

In 1856 the first mineral discoveries of the Morenci/Clifton area were found by California volunteers pursuing Apaches, and conflicts between the Apaches and advancing Anglo settlers touched off a 26-year-long war. Mining for gold and silver began in 1864, followed by copper in 1872, and the mine at Morenci quickly grew to become the largest copper producer in North America. Clifton's population ballooned from 600 in 1880 to 5000 by 1910, and it quickly earned its reputation as the wildest of the "Wild West" boomtowns. Neighboring Morenci was swallowed up by an open pit mine in the 1960s, but Clifton was preserved, and today Chase Creek Street is still graced with lovely Victorian-era buildings from the town's halcyon days as the place to quickly make and lose a fortune.

In 1983, Clifton survived two nearly fatal blows, first a nearly three-year-long strike that began on June 30, 1983. Then later that same year, on October 2, 1983, Tropical Storm Octave sent 90,900 cubic feet of water per second into the San Francisco River, which burst its banks, destroying 700 homes and heavily damaging 86 of the town's 126 businesses.

In the early 1900s, Clifton was the wildest town in the territory, according the Arizona Rangers and the Denver Tribune.

"There was a Sheriff, Justice of Peace, Mayor and a Town Council of sort, but if they were not all members of Kid Louis' gang, they were so afraid of him that they done what he said"; the company doctor, however, insisted that the killings had never averaged more than three a week.... All the men and some of the women owned rifles if not pistols, and there was easy access to dynamite... Justice of the Peace Boyles was busy, hearing sixteen cases of criminal violence in one summer month of 1904."

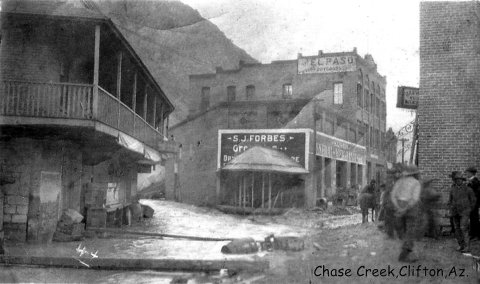

Chase Creek consisted of a creek, usually dry, paralleled by a dirt road — which meant, depending on the season, either dust, mud or flood — with building entrances four to six feet above street level to protect them from floods. Every six months Rosario (Challo) Olivas plowed the street with his steam to smooth the ruts (later the town acquired a one-cylinder Fairbank Morse stream roller to follow up."

Courtesy of the Greenlee County Historical Society and Clifton Historian Don Lunt

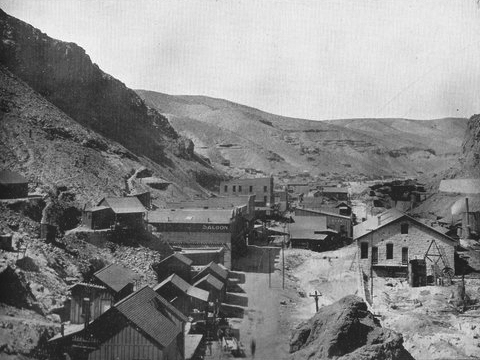

Chase Creek Street prior to 1902, with dirt streets and a wash on the north side of the street where buildings stand today.

Chase Creek Street prior to 1902, with dirt streets and a wash on the north side of the street where buildings stand today.

Barrels float down Chase Creek Street near the intersection Palicio, c 1903. Early Clifton was plagued by recurrent floods. The worst was in

1906, when a tailings dam broke and cascaded down Chase Creek. 18 people lost their lives and the flood damage was so great

that there was talk of abandoning the town.

Barrels float down Chase Creek Street near the intersection Palicio, c 1903. Early Clifton was plagued by recurrent floods. The worst was in

1906, when a tailings dam broke and cascaded down Chase Creek. 18 people lost their lives and the flood damage was so great

that there was talk of abandoning the town.

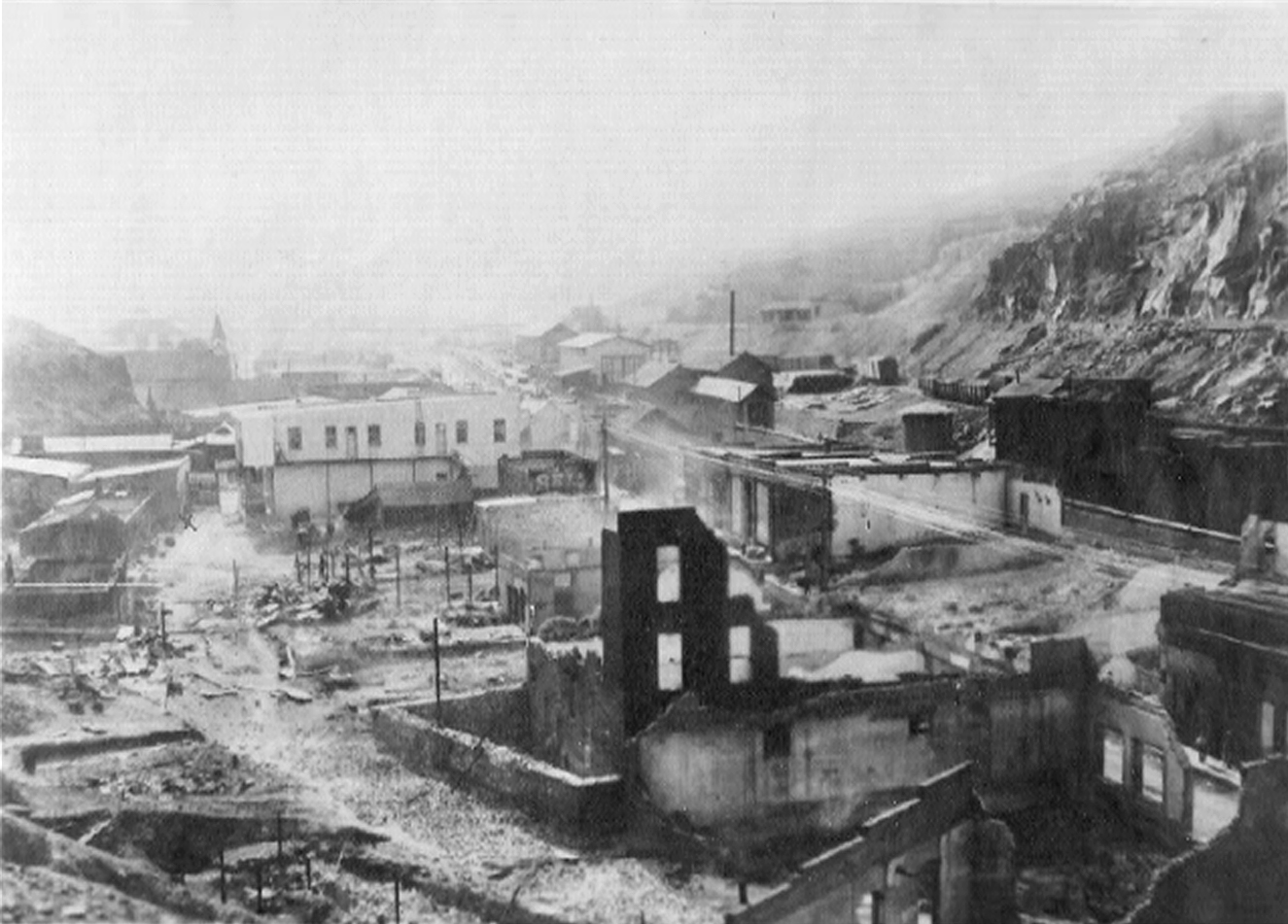

A fire roared through the Chase Creek Business District on April 7, 1913. Five lives and 25 structures were lost to the fire.

A fire roared through the Chase Creek Business District on April 7, 1913. Five lives and 25 structures were lost to the fire.

In the 1840s, Irish immigrants flooded into New York City on the heels of the Great Famine. They often lived in overcrowded tenements with poor sanitary conditions. Disease, poverty and crime plagued the Irish ghettos, and the children lived in deplorable conditions. In 1853 a group of social reformers founded the Children's Aid Society to provide relief for the poor and orphaned children of New York, Boston and other coastal cities. Their solution was to resettle them with farm families in the West to deter them from a life of crime and poverty. Between 1854 and 1929, more than 250,000 children were placed on "Orphan Trains" that stopped at more than 45 states across the country, as well as Canada and Mexico.

On October 1, 1904, one of those trains delivered 40 Irish orphans accompanied by three nuns and four nurses to Clifton, Arizona, to be placed in Catholic homes selected by the local priest. At that time, of course, most Catholic families were Mexican. The sight of those white toddlers being handed over to brown-skinned Hispanics infuriated Clifton's Anglo community. Within hours of the orphans' arrival, a mob had gathered and a posse of 25 vigilantes stormed the Mexican homes and kidnapped the children. The young priest was ridden out of town, and while the nuns and 21 of the children escaped, the rest remained, permanently, with their new white, non-Catholic families. The case was a media sensation, eventually making it way to Arizona Supreme Court, but the case was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.

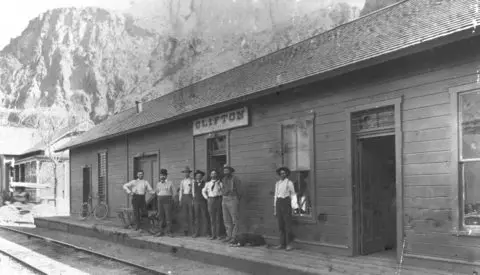

The Old Clifton Train Station ©Greenlee County Historical Society

The Old Clifton Train Station ©Greenlee County Historical Society

As a mining community, Clifton has experienced numerous strikes, most notably in 1903, 1915-1916 and 1967-1968. But a strike began on June 30, 1983, that some say spelled the end of organized labor in the United States. Many books have been written about the strike, which ended when Arizona Governor Bruce Babbitt ordered a military intervention in Clifton to "keep the peace." The strike is commemorated with a 40 x 10 mural at the Clifton Union Hall.

MoreTeresa Urrea, also known as "Santa Teresa" or "Santa Teresita de Cabora", was a traditional healer and political leader who spent the final years of her life in Clifton, Arizona. Teresa Urrea was born on a hacienda in Sinaloa, Mexico, in 1873, the illegitimate child of the Don Tomás Urrea, and the 14-year-old daughter of a Tehueco Indian ranch hand, Cayetana Chávez. Don Tomás was a wealthy rancher and outspoken liberal who ran afoul of Mexican dictator Porfirio Diáz. One day, possibly after escaping an attempted rape, Teresita suffered a seizure that left her semi-comatose for weeks or months. When she recovered, she began performing healings by laying her hands on the sick and disabled. Rumors of miraculous cures spread quickly, and thousands of pilgrims made the journey to Cabora. The Mexican Catholic church denounced Urrea, but her simple message of justice inspired Indian peasants to resist seizure of their lands by Diáz and his allies. Blamed for inciting a rebellion in Tomochic, Urrea and her father were deported in 1892, and over the next four years they fled to Nogales and eventually to Clifton, Arizona.

In June of 1900, Teresa married Guadalupe Rodríguez, a Yaqui Indian who worked in the copper mines. But the day after their wedding Rodríguez insisted at gunpoint that Teresa accompany him back to Mexico — perhaps to collect the bounty. She escaped and Rodríguez was arrested.

Teresita's reputation expanded to the Anglo community after she healed the six-year-old son of Clifton banker Charles Rosecrans. Mrs. Rosecrans took her to San Francisco where a local businessman began marketing her services as a faith healer. Returning to Clifton in 1904, Teresa used the money she had earned to build a hospital. But her curative powers had diminished, and she died in 1906, apparently of consumption, at just 33 years of age. She is buried there beside her father.

Sources:

"The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction," Linda Gordon (Harvard University Press, 1999)

"Handbook of Texas Online", Frances Mayhugh Holden

Teresa de Urrea

Accounts of Teresa Urrea may be found in the following books:

Griffith, James S. Victims, Bandits, and Healers: Folk Saints of the Borderlands. Rio Nuevo Publishers, Tucson, 2003. Chapter 3.

Holden, William Curry. Teresita. Owings Mills, Maryland: Stemmer House, 1978.

Urrea, Luis Alberto. The Hummingbird's Daughter. Little, Brown, 2005.

Agnes Smedley

"Daughter of Earth," Agnes Smedley (Harvard University Press, 1999)

"Agnes Smedley: The Life and Times of an American Radical," James R. McKinnon and Stephen R. MacKinnon (University of California Press, 1988)

Agnes Smedley, an American journalist, author and activist, had an early connection to Clifton, Arizona.

Smedley was raised in a poverty-stricken miner's family in Missouri and Colorado, and she catalogued the evolution of her socialist and feminist and consciousness in the autobiographical "Daughter of Earth" (1929).

After brief but disastrous stints as a secretary and a magazine sales agent, Smedley reached out to Big Buck, a 42-year-old cowboy who had worked for her father.

When the cattle business began to decline, Buck had become a mechanic in the copper-mining town of Clifton, Arizona. In Colorado, Big Buck had taught Agnes to shoot, ride, lasso, and do tricks with a jacknife. She later wrote that he 'had tried hard to blast out of me everything feminine,' and that he was the one man she felt she could trust ...'

Big Buck sent Agnes the money for a train ticket to Clifton. He arranged for her to stay in his hotel and introduced her to all as his sister, and bought her meals at the Chinese restaurant across the street.

The high desert mining town made quite an impression on the young Agnes Smedley:

The town lay in a canyon cut in two by a flowing river, though where the river came from is beyond my imagination. On one side arose a wall of almost solid stone, on the other a steep, barren mountainside on which no tree could grow. During the day the blistering midday sun heated the stone wall and it was long past midnight before the air cooled. Our hotel boasted the only sidewalk in the town — a board walk that stopped when the hotel stopped. Down the street stood a rambling shed — the Chinese laundry where I learned to swear in Chinese and to sprinkle clothing by squirting water from my mouth — both no easy accomplishments. Up the street and along one side of the river lay a row of little, unpainted one-story houses. Beyond, blocking the canyon, towered the dark buildings of the copper works, and further beyond, the mines. Above, on top of the mountain ridge, lay a part of the trail where the warriors of Geronimo, the Apache chief, had one guarded this pass against white invaders. Beyond the trial stretched an endless series of brooding, rugged hills, devoid of life, and to the north a range of black, forbidding mountains. A world deserted by man, inhabited by rattle snakes, lizards, and gila monsters. The sun beat down on the black stony hills until they were frying hot. Hell must be such a place as this."

Big Buck's friendship was not entirely platonic. He proposed to Agnes after she began spending time with a young Mormon forest ranger. Agnes demurred, claiming she would never marry. Undeterred, Big Buck offered to front her the money for six months of training at a teacher's college in Tempe, hoping that after that she would return to Clifton and take him up on his marriage proposal. But Smedley stuck to her guns, and when the six months had passed, Big Buck rode off to join the Mexican Revolution.

Smedley would go on to dedicate her life to the support of independence movements in India and China. In addition to Daughter of Earth, Smedley's publications include four non-fiction books on China; reportage for newspapers in the United States, England, and Germany; and a biography of the Chinese communist general Zhu De.